What is IoT? The internet of things explained

The internet of things (IoT) is a catch-all term for the growing number of electronics that aren’t traditional computing devices, but are connected to the internet to send data, receive instructions or both.

There’s an incredibly broad range of things that fall under that umbrella: Internet-connected “smart” versions of traditional appliances like refrigerators and light bulbs; gadgets that could only exist in an internet-enabled world like Alexa-style digital assistants; internet-enabled sensors that are transforming factories, healthcare, transportation, distribution centers and farms.

What is the internet of things?

The IoT brings the power of the internet, data processing and analytics to the real world of physical objects. For consumers, this means interacting with the global information network without the intermediary of a keyboard and screen; many of their everyday objects and appliances can take instructions from that network with minimal human intervention.

[ More IoT coverage of Network World ]

In enterprise settings, IoT can bring the same efficiencies to physical manufacturing and distribution that the internet has long delivered for knowledge work. Millions if not billions of embedded internet-enabled sensors worldwide are providing an incredibly rich set of data that companies can use to gather data about their safety of their operations, track assets and reduce manual processes. Researchers can also use the IoT to gather data about people’s preferences and behavior, though that can have serious implications for privacy and security.

How big is it?

In a word: enormous. Priceonomics breaks it down: There are more than 50 billion IoT devices as of 2020, and those devices will generate 4.4 zettabytes of data this year. (A zettabyte is a trillion gigabytes.) By comparison, in 2013 IoT devices generated a mere 100 billion gigabytes. The amount of money to be made in the IoT market is similarly staggering; estimates on the value of the market in 2025 range from $1.6 trillion to $14.4 trillion.

History of IoT

A world of omnipresent connected devices and sensors is one of the oldest tropes of science fiction. IoT lore has dubbed a vending machine at Carnegie Mellon that was connected to APRANET in 1970 as the first Internet of Things device, and many technologies have been touted as enabling “smart” IoT-style characteristics to give them a futuristic sheen. But the term Internet of Things was coined in 1999 by British technologist Kevin Ashton.

At first, the technology lagged behind the vision. Every internet-connected thing needed a processor and a means to communicate with other things, preferably wirelessly, and those factors imposed costs and power requirements that made widespread IoT rollouts impractical, at least until Moore’s Law caught up in the mid ’00s.

One important milestone was widespread adoption of RFID tags, cheap minimalist transponders that could be stuck on any object to connect it to the larger internet world. Omnipresent Wi-Fi and 4G made it possible to for designers to simply assume wireless connectivity anywhere. And the rollout of IPv6 means that connecting billions of gadgets to the internet won’t exhaust the store of IP addresses, which was a real concern. (Related story: Can IoT networking drive adoption of IPv6?)

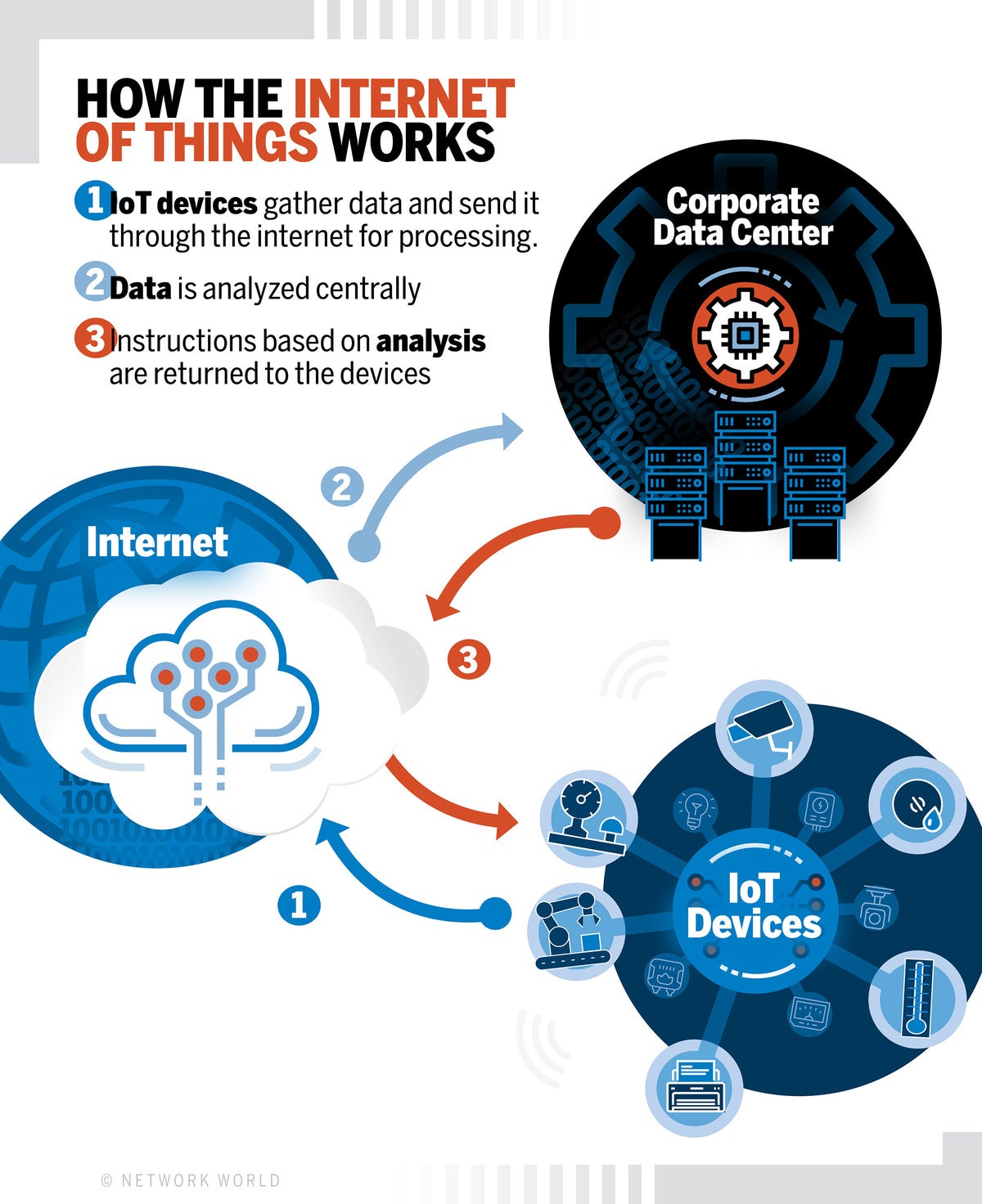

How does the IoT work?

The basic elements of the IoT are devices that gather data. Broadly speaking, they are internet-connected devices, so they each have an IP address. They range in complexity from autonomous vehicles that haul products around factory floors to simple sensors that monitor the temperature in buildings. They also include personal devices like fitness trackers that monitor the number of steps individuals take each day. To make that data useful it needs to be collected, processed, filtered and analyzed, each of which can be handled in a variety of ways.

Collecting the data is done by transmitting it from the devices to a gathering point. Moving the data can be done wirelessly using a range of technologies or on wired networks. The data can be sent over the internet to a data center or a cloud that has storage and compute power or the transfer can be staged, with intermediary devices aggregating the data before sending it along.

Processing the data can take place in data centers or cloud, but sometimes that’s not an option. In the case of critical devices such as shutoffs in industrial settings, the delay of sending data from the device to a remote data center is too great. The round-trip time for sending data, processing it, analyzing it and returning instructions (close that valve before the pipes burst) can take too long. In such cases edge-computing can come into play, where a smart edge device can aggregate data, analyze it and fashion responses if necessary, all within relatively close physical distance, thereby reducing delay. Edge devices also have upstream connectivity for sending data to be further processed and stored.

How the internet of things works.

Examples of IoT devices

Essentially, anything that’s capable of gathering some information about the physical world and sending it back home can participate in the IoT ecosystem. Smart home appliances, RFID tags, and industrial sensors are a few examples. These sensors can monitor a range of factors including temperature and pressure in industrial systems, status of critical parts in machinery, patient vital signs, and use of water and electricity, among many, many other possibilities.

Entire factory robots can be considered IoT devices, as can autonomous vehicles that move products around industrial settings and warehouses.

Other examples include fitness wearables and home security systems. There are also more generic devices, like the Raspberry Pi or Arduino, that let you build your own IoT end points. Even though you might think of your smartphone as a pocket-sized computer, it may well also be beaming data about your location and behavior to back-end services in very IoT-like ways.

Device management

In order to work together, all those devices need to be authenticated, provisioned, configured, and monitored, as well as patched and updated as necessary. Too often, all this happens within the context of a single vendor’s proprietary systems – or, it doesn’t happen at all, which is even more risky. But the industry is starting to transition to a standards-based device management model, which allows IoT devices to interoperate and will ensure that devices aren’t orphaned.

IoT communication standards and protocols

When IoT gadgets talk to other devices, they can use a wide variety of communications standards and protocols, many tailored to devices with limited processing capabilities or not much electrical power. Some of these you’ve definitely heard of — some devices use Wi-Fi or Bluetooth, for instance — but many more are specialized for the world of IoT. ZigBee, for instance, is a wireless protocol for low-power, short-distance communication, while message queuing telemetry transport (MQTT) is a publish/subscribe messaging protocol for devices connected by unreliable or delay-prone networks. (See Network World’s glossary of IoT standards and protocols.)

The increased speeds and bandwidth of the coming 5G standard for cellular networks will also benefit IoT, though that usage will lag behind ordinary cell phones.

IoT, edge computing and the cloud

How edge computing enables IoT.

For many IoT systems, there’s a lot of data coming in fast and furious, which has given rise to a new technology category, edge computing, consisting of appliances placed relatively close to IoT devices, fielding the flow of data from them. These machines process that data and send only relevant material back to a more centralized system for analysis. For instance, imagine a network of dozens of IoT security cameras. Instead of bombarding the building’s security operations center (SoC) with simultaneous live-streams, edge-computing systems can analyze the incoming video and only alert the SoC when one of the cameras detects movement.

And where does that data go once it’s been processed? Well, it might go to your centralized data center, but more often than not it will end up in the cloud.

The elastic nature of cloud computing is great for IoT scenarios where data might come in intermittently or asynchronously. And many of the big cloud heavy hitters — including Google, Microsoft, and Amazon — have IoT offerings.

IoT platforms

The cloud giants are trying to sell more than just a place to stash the data your sensors have collected. They’re offering full IoT platforms, which bundle together much of the functionality to coordinate the elements that make up IoT systems. In essence, an IoT platform serves as middleware that connects the IoT devices and edge gateways with the applications you use to deal with the IoT data. That said, every platform vendor seems to have a slightly different definition of what an IoT platform is, the better to distance themselves from the competition.

IoT and data

As mentioned, there are zettabytes of data being collected by all those IoT devices, funneled through edge gateways, and sent to a platform for processing. In many scenarios, this data is the reason IoT has been deployed in the first place. By collecting information from sensors in the real world, organizations can make nimble decisions in real time.

Oracle, for instance, imagines a scenario where people at a theme park are encouraged to download an app that offers information about the park. At the same time, the app sends GPS pings back to the park’s management to help predict wait times in lines. With that information, the park can take action in the short term (by adding more staff to increase the capacity of some attractions, for instance) and the long term (by learning which rides are the most and least popular at the park).

These decisions can be made without human intervention. For example, data gathered from pressure sensors in a chemical-factory pipeline could be analyzed by software in an edge device that spots the threat of a pipeline rupture, and that information can trigger a signal to shut valves to avert a spill.

IoT and big data analytics

The theme park example is easy to get your head around, but is small potatoes compared to many real-world IoT data-harvesting operations. Many big data operations use information harvested from IoT devices, correlated with other data points, to get insight into human behavior. Software Advice gives a few examples, including a service from Birst that matches coffee brewing information collected from internet-connected coffeemakers with social media posts to see if customers are talking about coffee brands online.

Another dramatic example came recently when X-Mode released a map based on tracking location data of people who partied at spring break in Ft. Lauderdale in March of 2020, even as the coronavirus pandemic was gaining speed in the United States, showing where all those people ended up across the country. The map was shocking not only because it showed the potential spread of the virus, but also because it illustrated just how closely IoT devices can track us. (For more on IoT and analytics, click here.

IoT data and AI

The volume of data IoT devices can gather is far larger than any human can deal with in a useful way, and certainly not in real time. We’ve already seen that edge computing devices are needed just to make sense of the raw data coming in from the IoT endpoints. There’s also the need to detect and deal with data that might be just plain wrong.

Many IoT providers are offering machine learning and artificial intelligence capabilities to make sense of the collected data. IBM’s Jeopardy!-winning Watson platform, for instance, can be trained on IoT data sets to produce useful results in the field of predicative maintenance — analyzing data from drones to distinguish between trivial damage to a bridge and cracks that need attention, for instance. Meanwhile, Arm is working on low-power chips that can provide AI capabilities on the IoT endpoints themselves.

IoT and business

Business uses for IoT include keeping track of customers, inventory, and the status of important components. IoT for All flags four industries that have been transformed by IoT:

- Oil and gas: Isolated drilling sites can be better monitored with IoT sensors than by human intervention

- Agriculture: Granular data about crops growing in fields derived from IoT sensors can be used to increase yields

- HVAC: Climate control systems across the country can be monitored by manufacturers

- Brick-and-mortar retail: Customers can be microtargeted with offers on their phones as they linger in certain parts of a store

More generally, enterprises are looking for IoT solutions that can help in four areas: energy use, asset tracking, security, and the customer experience.

READ MORE HERE

![Network World - How Edge Computing Works [diagram]](https://images.idgesg.net/images/article/2017/09/nw_how_edge_computing_works_diagram_1400x1717-100736111-large.jpg)