Is KAX17 Performing De-Anonymization Attacks Against Tor Users?

After I reported the exit relays (at the time I did not know they are part of KAX17) they got removed in October 2020, but I do not believe that halted their exit operations completely. Coincidentally a new large no-name exit relay group was born the day after their removal. That new group is not included in figure 1 because it can not be attributed to KAX17 using the same strong indicator.

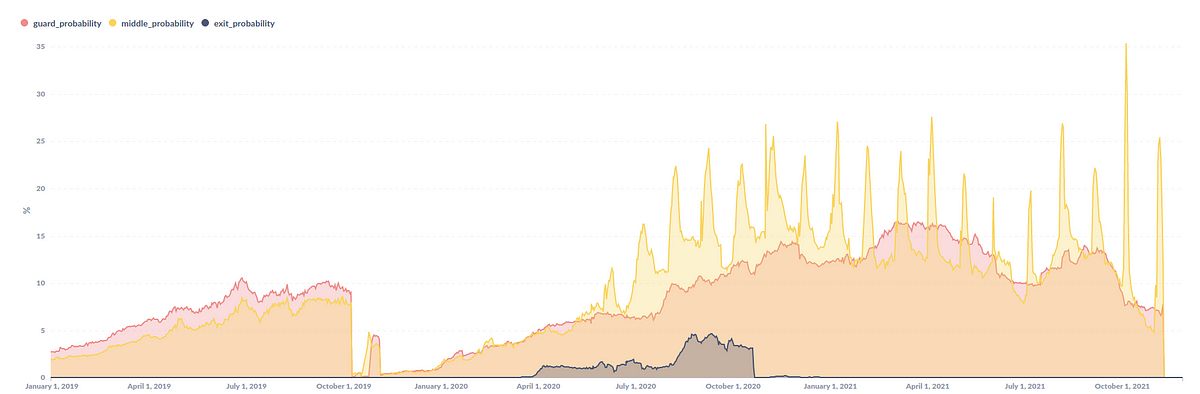

To provide a worst-case snapshot, on 2020–09–08 KAX17’s overall tor network visibility would allow them to de-anonymize tor users with the following probabilities:

- first hop probability (guard) : 10.34%

- second hop probability (middle): 24.33%

- last hop probability (exit): 4.6%

As middle and exit relays are frequently changed the likelihood to use KAX17’s relays increases with tor usage over time. We have no evidence, that they are actually performing de-anonymization attacks, but they are in a position to do so and the fact that someone runs such a large network fraction of relays “doing things” that ordinary relays can not do (intentionally vague), is enough to ring all kinds of alarm bells.

In the course of 2020 large amounts of suspicious non-exit relays joined the network and were reported to the Tor Project, but since they no longer got removed, I sent them to the public tor-talk mailing list as their capacity continued to increase (2020–08–20, 2020–09–22).

The unexpected hint towards a better understanding of the mystery

At the time (2020) I had no strong linkability indicators for these large sets of non-exit relays to the KAX17 actor – that changed a few weeks ago (fall 2021), when a reader of this blog, reached out to share their notes about a suspicious group of relays. We independently verified and reproduced their observations on a technical level. When put into the broader context, their hint helped to understand the bigger picture by providing strong indicators that all those relays:

- are in fact operated by a single entity and

- all of them are actually part of KAX17.

What is special about KAX17?

KAX17 is more worrisome than the usual malicious tor exit relay group, because they appear to be rather keen on having a large visibility into non-exit positions of the network (entry guard and middle relay). These positions are useless for the usual malicious actor manipulating and sniffing tor exit traffic, because in these positions no plaintext traffic is available. Actors performing attacks in these non-exit positions are considered more advanced adversaries because these attacks require a higher sophistication level and are less trivial to pull off.

Some parts of this story reminded me of the so called “relay early” traffic confirmation attack from back in 2014 that combined running malicious relays with active tor protocol level exploitation to de-anonymize onion services (at the time called “hidden services”) and their users, because that was one of these rare cases where you also got to see attacks involving non-exit relays. Other than that there is nothing pointing in that direction.

KAX17’s involvement in tor-relays policy discussions

When looking over KAX17 relays’ metadata I repeatedly came across a particular email address. Some of KAX17’s relays initially had used that email address in their ContactInfo but soon after these relays were setup the email address got removed from their configuration. I also came across this email address on the tor-relays mailing list. Interestingly it became almost exclusively involved on the mailing list when policy proposals with regards to malicious relays were discussed or when large malicious relay groups got removed. They apparently disliked the proposals to make their activities less effective 🙂

Since everyone can use your email address in their relay’s ContactInfo, that information is not necessarily authentic, but since the email address has been used on KAX17 relays long before it first appeared on the tor-relays mailing list I guess that was just poor OPSEC on their part.

It is apparent that tor users have powerful adversaries with a lot of resources at their hands. It is a particularly uncomfortable situation to be in, knowing some actor has been running large fractions of the tor network for years and will continue to do so. It is also clear that we can not detect— let alone get removed — even such large scale relay groups in a timely manner. KAX17’s operations likely got severely degraded when the tor directory authorities took actions against them in November 2021, but they already started to restore their foothold, like they did after their first removal in October 2019, so we will need some more sustainable solutions when dealing with malicious relays.

In the past I have always been reluctant to make tor client configuration changes that affect path selection because it makes a tor client theoretically stand out, but in the light of the tor network’s threat landscape I consider it a reasonable (for some threat model even a necessary) act of self-defense to stop using untrusted relays for certain path positions to reduce the risk of de-anonymization and other types of attacks — even if that is a non-default configuration.

To achieve that goal tor clients would need to:

(1) configure trusted operators or learn about them via so called trust anchors

(2) automatically enumerate all relays of trusted operators

(3) automatically configure the tor client to use only trusted relays for certain positions like entry guard and/or exit relay

The design allows tor users to assigns trust at the operator level and inherits that trust to all the relays an operator manages. This should ensure scalability and be less fragile to changes like when new relays get added or replaced.

Non-spoofable operator identifiers

How do we tackle (2)? The tor network has no identifiers for relay operators. There is a relay’s ContactInfo string, but using that without any verification scheme is not safe and has been exploited by malicious operators in the past. So we need some operator identifiers that can not be spoofed arbitrarily by an adversary. Luckily we are not unprepared for that. In 2020 I wrote a specification (CIISS) that allows tor relay operators to link their relays to their domain/hostname in a verifiable way. That is accomplished using a simple 2-way link from the relay to a domain and from the domain back to a relay. In practice an operator has to perform two simple steps to link her relay to her domain in a non-spoofable way according to the specification:

- add

url:example.com proof:uri-rsa ciissversion:2

to her relay’s ContactInfo - publish the relay’s fingerprint at the IANA registered well-known URI:

https://example.com/.well-known/tor-relay/rsa-fingerprint.txt

(or create a DNS TXT record).

In the past few months the proven domain has already been widely implemented by most large exit operators of the tor relay community and currently over 50% of the tor network’s exit capacity is covered (more is better):

This provides tor users with non-spoofable automatically verifiable operator identifiers they can assign trust to. It is important to stress the point that proven domains are not implicitly trusted, malicious groups can also proof their domain. It is only the first step, an identifier that users can choose to trust. The adoption of the proven operator domain for guard relays is significantly lower (~10% guard probability), until that fraction increases users could configure a trusted relay as a bridge to reduce their chance of using malicious guards.

Trusting operator domains

Trust in this context means that a relay operators is believed to operate relays without malicious intent. The details of publishing and consuming trust information are laid out in this specification draft: A Simple Web of Trust for Tor Relay Operator IDs. It allows the (optional) dynamic discovery of trusted operators starting from a trust anchor, but it also supports stricter manual only trust assignments (without recursive discovery)— it is up to the user to decide.

Proof of concept implementation

We’ve implemented a quick and dirty proof of concept of the steps outlined above and are publishing it with this blog post. It is not meant for general use by end-users.

https://github.com/nusenu/trustor-poc

It is implemented as a python script that talks to the local tor client via its control port/socket, reads the local file with a list of trusted operator domains, verifies relay/domain proofs (via tor) and configures the tor client to use exit relays run by trusted operators only. The list of trusted operators is defined by the user.

We would like to implement an actual serious implementation and we might have an update on that within the next months.

- A mysterious actor which we gave the code-name KAX17 has been running large fractions of the tor network since 2017, despite multiple attempts to remove them from the network during the past years.

- KAX17 has been running relays in all positions of a tor circuit (guard, middle and exit) across many autonomous systems putting them in a position to de-anonymize some tor users.

- Their actions and motives are not well understood.

- We found strong indicators that a KAX17 linked email address got involved in tor-relays mailing list discussions related to fighting malicious relays.

- Detecting and removing malicious tor relays from the network has become an impractical problem to solve.

- We presented a design and proof of concept implementation towards better self-defense options for tor clients to reduce their risk from malicious relays without requiring their detection.

- Most of the tor network’s exit capacity (>50%) supports that design already. More guard relays adopting the proven domain are needed (currently at around 10%).

I’d like to thank the person who provided crucial input towards a better understanding KAX17’s relays. The person asked to remain anonymous.

The following graph shows KAX17’s network capacity (at least the one we know about). The detection method has certainly false-negatives (there are relays we did not attribute to them).

READ MORE HERE