Ars Technica Used In Malware Campaign With Never-Before-Seen Obfuscation

Ars Technica was recently used to serve second-stage malware in a campaign that used a never-before-seen attack chain to cleverly cover its tracks, researchers from security firm Mandiant reported Tuesday.

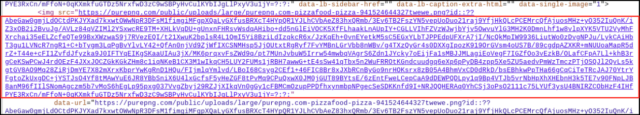

A benign image of a pizza was uploaded to a third-party website and was then linked with a URL pasted into the “about” page of a registered Ars user. Buried in that URL was a string of characters that appeared to be random—but were actually a payload. The campaign also targeted the video-sharing site Vimeo, where a benign video was uploaded and a malicious string was included in the video description. The string was generated using a technique known as Base 64 encoding. Base 64 converts text into a printable ASCII string format to represent binary data. Devices already infected with the first-stage malware used in the campaign automatically retrieved these strings and installed the second stage.

Not typically seen

“This is a different and novel way we’re seeing abuse that can be pretty hard to detect,” Mandiant researcher Yash Gupta said in an interview. “This is something in malware we have not typically seen. It’s pretty interesting for us and something we wanted to call out.”

The image posted on Ars appeared in the about profile of a user who created an account on November 23. An Ars representative said the photo, showing a pizza and captioned “I love pizza,” was removed by Ars staff on December 16 after being tipped off by email from an unknown party. The Ars profile used an embedded URL that pointed to the image, which was automatically populated into the about page. The malicious base 64 encoding appeared immediately following the legitimate part of the URL. The string didn’t generate any errors or prevent the page from loading.

Mandiant researchers said there were no consequences for people who may have viewed the image, either as displayed on the Ars page or on the website that hosted it. It’s also not clear that any Ars users visited the about page.

Devices that were infected by the first stage automatically accessed the malicious string at the end of the URL. From there, they were infected with a second stage.

The video on Vimeo worked similarly, except that the string was included in the video description.

Ars representatives had nothing further to add. Vimeo representatives didn’t immediately respond to an email.

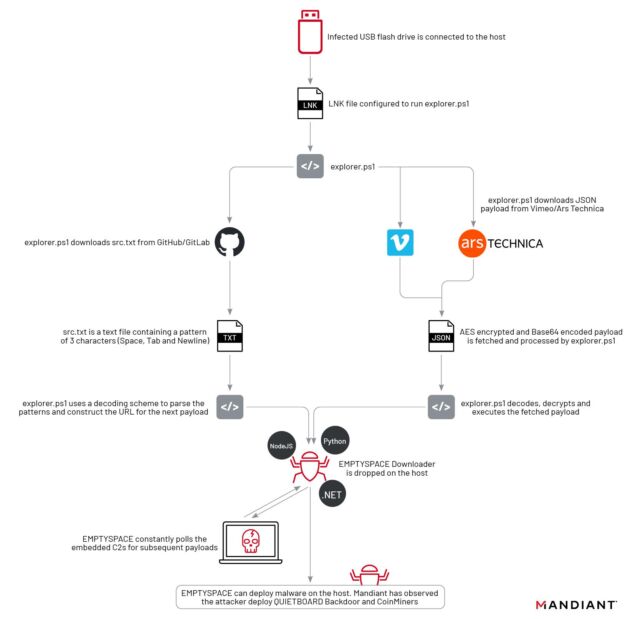

The campaign came from a threat actor Mandiant tracks as UNC4990, which has been active since at least 2020 and bears the hallmarks of being motivated by financial gain. The group has already used a separate novel technique to fly under the radar. That technique spread the second stage using a text file that browsers and normal text editors showed to be blank.

Opening the same file in a hex editor—a tool for analyzing and forensically investigating binary files—showed that a combination of tabs, spaces, and new lines were arranged in a way that encoded executable code. Like the technique involving Ars and Vimeo, the use of such a file is something the Mandiant researchers had never seen before. Previously, UNC4990 used GitHub and GitLab.

The initial stage of the malware was transmitted by infected USB drives. The drives installed a payload Mandiant has dubbed explorerps1. Infected devices then automatically reached out to either the malicious text file or else to the URL posted on Ars or the video posted to Vimeo. The base 64 strings in the image URL or video description, in turn, caused the malware to contact a site hosting the second stage. The second stage of the malware, tracked as Emptyspace, continuously polled a command-and-control server that, when instructed, would download and execute a third stage.

Mandiant has observed the installation of this third stage in only one case. This malware acts as a backdoor the researchers track as Quietboard. The backdoor, in that case, went on to install a cryptocurrency miner.

Anyone who is concerned they may have been infected by any of the malware covered by Mandiant can check the indicators of compromise section in Tuesday’s post.

READ MORE HERE